|

.

1 | Music In The Modern Era

Music and Technology

Peter

Kun Frary

.

The music industry underwent a rapid revolution in the early twentieth century as new technologies for recording and distribution of music undermined traditional performance and publication. We'll examine these changes and the emerging technologies behind them.

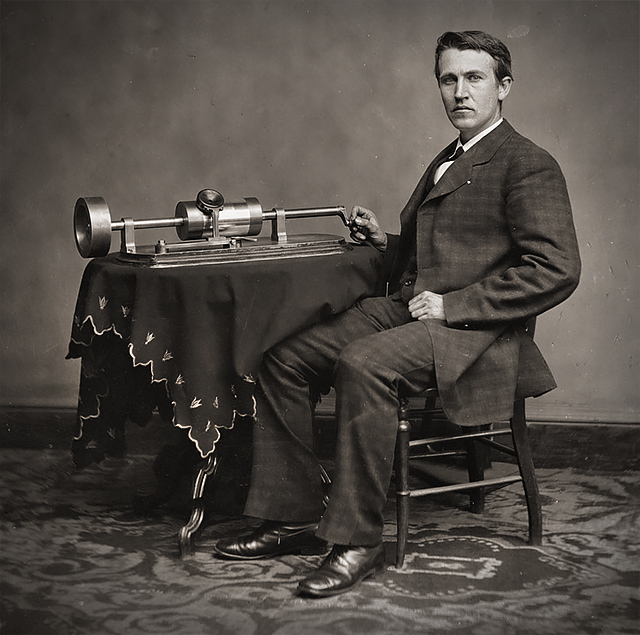

Thomas Edison (1878) and cylinder phonograph | Library of Congress

New Music Media New Music Media

Before the advent of audio recording, music was shared through music notation and live performance. Mechanical music boxes and player pianos existed, but these devices were expensive novelty items and not in widespread use.

Phonograph Phonograph

A revolution in music distribution and consumption began with the invention of the phonograph in 1878. In 1904, the first commercial recordings of music appeared. The stage was now set for mass distribution and merchandising of music. The phonograph, a playback device for the LP or phonograph record, is still popular for music listening a century and a half after its invention.

Radio Radio

Radio broadcasts of entertainment began in the United Kingdom in 1920. Radio stations programmed the latest phonograph records, increasing the popularity of musicians and phonograph technology.

Within a generation, radio and phonograph use skyrocketed, bringing music to remote corners of the Earth. The influence of these new methods of distribution was profound: creation of vast audiences and distribution networks, reduction of live performance opportunities for local musicians, declining sheet music sales, and rapid changes in musical styles.

Although radio is waning in the twenty-first century, mass consumption of music continues with web-based platforms such as streaming and downloads.

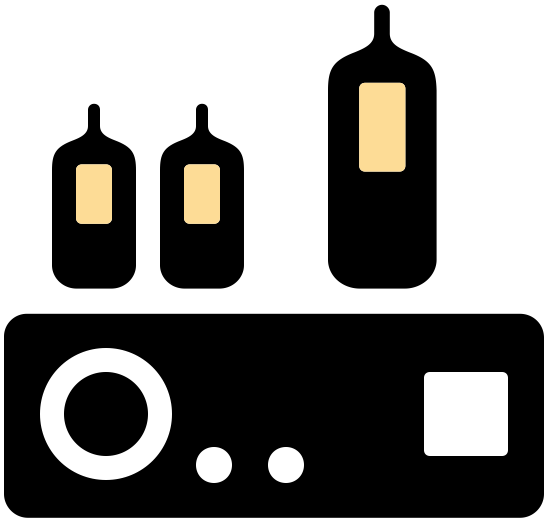

Vacuum Tube | Groove Tube GT-12AU7 | Tube design hasn't changed much since the 1950s. I pulled this one from a 1995 Trace Elliot guitar amplifier.

Audio Amplifiers Audio Amplifiers

Invention of the triode vacuum tube in 1907 by Lee De Forest is tied to the success of radio, audio recording, and performing. The vacuum tube is a device that controls electric current flow in a vacuum between electrodes. The triode added voltage gain control—amplification of the signal. Thus was born the audio amplifier, with prototypes appearing in 1912. Vacuum tubes were used in radio, television, and sound reinforcement until largely displaced by transistors during the 1960s. Vacuum tubes are still used in guitar amplifiers and audiophile gear.

Takamine Guitar | Audio amplifiers and microphones made it possible for soft instruments to be heard in large venues such as concert halls and stadiums.

The significance of the audio amplifier is twofold for music:

- Small ensembles and soft instruments could perform in large venues.

- Recorded music could be played in any location with electricity, including automobiles, mass transit, homes and businesses.

One effect of amplifier use was the decline of large ensembles such as orchestras and brass bands, and subsequent reduction of music performance jobs. Now a concert or dance hall could be filled with sound from a handful of musicians. It was once common for radio stations to employ staff musicians; some even had orchestras on payroll. Radio stations and businesses gradually moved away from live musicians and used recorded music for convenience and reduced cost.

Genz Benz Shenandoah Guitar Amplifier | Photo courtesy Genz Benz

Stylistic Changes Stylistic Changes

Audio amplifiers had a significant effect on musical style and technique, spawning singing and instrumental styles unimagined in the prior centuries of acoustic performance. There would be no shearing guitar solos or balancing of soft vocals with drums and brass instruments if it were not for microphones and amplifiers.

Electrophones Electrophones

Invention and use of electrophones, i.e., electronic musical instruments, followed audio amplifiers. Electrophones produce sound using electronics: an electrical audio signal is output, processed, and amplified through an audio system.

Most electronic instruments are based on modified acoustic instruments, e.g., electric guitar and bass guitar. Others are purely electronic, such as computers, samplers, and synthesizers. Electronic musical instruments were not significant until the second half of the twentieth century and, indeed, have little role in classical, non-Western, and folk music. However, telephones are extremely important in recent popular music styles, computer games, and film.

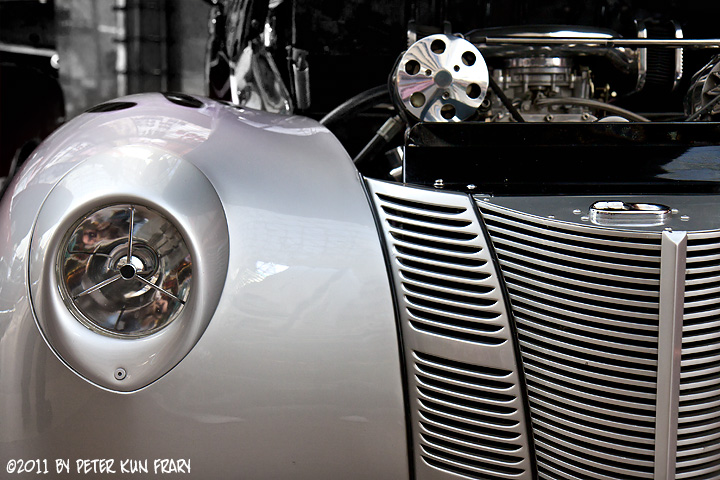

1940 Ford | The advent of automobiles, trains and airplanes made the world smaller and hastened the spread of culture.

Transportation Transportation

In earlier eras, musicians could only travel via foot, horse, or ship. The rise of rapid transportation—rail, highway, and air travel networks—opened new possibilities and made the world more accessible. People were freer than any time in history to choose where to live, travel, and how to spend leisure time. Musicians were able to quickly and relatively inexpensively tour, sharing musical influences across the globe. The Spanish guitar virtuoso, Andrés Segovia (1893-1987), toured every inhabited continent during the first half of the twentieth century, popularizing the guitar across the globe. The Japanese Imperial Court Orchestra in New York and a Hawaiian slack key festival in Seattle are just a few performances never thought possible before the twentieth century.

Rapid transportation and recording media did more than hasten Western cultural colonization of the world. Western artists were influenced by folk and popular music of Asia, Africa, and other non-Western societies. These influences echo in the music of Ravel, Stravinsky, and other early twentieth-century composers. Indeed, these influences are still heard today in the World Beat genre.

Hawaiian Air | Air travel made touring practical for musicians | ©Peter Frary

Early Twentieth Century Style Early Twentieth Century Style

The twentieth century was an era of musical diversity. During the prior century, composers grew increasingly individualistic, stretching stylistic constraints to the breaking point. As the twentieth century dawned, this individualistic trend accelerated: musical styles multiplied and evolved rapidly, never again to conform to a single stylistic standard. In some cases, stylistic changes were so rapid and radical that audiences were confused and offended, forcing avant-garde artists to retreat into academia or, in the case of Russia, Germany, and China, flee their homeland to avoid persecution. Many of these artists were given asylum in the United States, enriching our universities as music professors and supplying Hollywood with hundreds of soundtrack scores.

Melody

Due to the extreme diversity of twentieth-century styles, there is not an exact definition of style elements. However, there are some broad generalizations we can make. For example, melody in twentieth-century art music tends to differ from earlier eras. The singable melodies of the Romantic and Classical eras were often considered old-fashioned and trite. The appearance of melodies with wide leaps, unusual phrase structures, unpredictable rhythm, and dissonant tones frequently replaced the pretty tunes of the Romantics. In some cases, melody was completely absent, leaving texture, rhythm, and timbre as the principal expressive features.

Harmony

The increased chromaticism of the late Romantic style harmony heralded the breakdown of functional harmony—the harmonic style used since the Baroque era. Twentieth-century composers purposely broke the rules of traditional harmony: decorative dissonance, unresolved chords, polytonality (two or more keys simultaneously), and choosing chords for color rather than function. The result of these changes was greatly increased dissonance and heightened tension for listeners. In some cases—Expressionism—a sense of key was completely dispensed with, creating music without a tonal center, i.e., atonal.

Rhythm

Prior to the twentieth century, rhythmic structure in Western art music revolved around symmetrical phrases organized within a single meter. Modern composers broke away from these conventions and embraced multi-metric (changing meters) and polymetric (two or more meters simultaneously) techniques, extreme use of syncopation, and, in some cases, non-metrical structure.

Timbre

In the absence of traditional melody and harmony, the expressive use of timbre, i.e., tone color, became increasingly important in modern music. New timbres were initially created by breaking the rules of orchestration. For example, using extreme ranges of traditional instruments such as the highest register of a violin or the lowest register of a clarinet. Unorthodox combinations of instruments—e.g., mandolin and tuba—also resulted in new tonal colors, as did the greatly increased use of percussion instruments in orchestras.

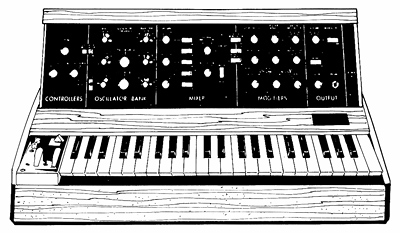

Synthesizer | Many timbres are available on synthesizers | Dover Clip Art

Traditional instruments were sometimes modified to create new timbres: mutes on string instruments and brass to create soft and distant colors; coins, bolts, and other objects placed on the strings of a piano to make randomized colors, etc. New timbres could also be created with nontraditional playing techniques such as striking the strings of a violin with a stick, snapping strings against the fingerboard, or playing a string or brass instrument like a percussion instrument by tapping or striking the body. Finally, in the second half of the twentieth century, electrophones greatly multiplied tone color possibilities.

The Vampire (1895) | Edvard Munch | Munch Museum, Oslo

Works by early twentieth-century composers often display stylistic traits beyond simple assaults on tonality and increased dissonance. Indeed, they feature extreme elements of musical violence and distortion—thumbing their noses at Classical and Romantic ideals of beauty and expression. After all, artists are a product of their environment. These traits are simply a reflection of the increasing mechanization, noise, and violence of modern life. Audiences were supposed to be disturbed from their complacency. You'll soon hear these unsettling traits in the bombastic and rollicking dissonances of Charles Ives, the "primitive" rhythms of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring, and the nightmare sounds of Schoenberg's Pierrot Lunaire.

Twentieth Century "-isms"

Impressionism, Expressionism, Primitivism, and Neoclassicism were among the first musical styles to challenge Romanticism at the turn of the century. They're also our parting topics for the final leg of our one-thousand-year journey. These styles are merely the beginning of a great century of music—the mammoth diversity of twentieth-century music is beyond the scope of this course. However, separate UH System courses on popular music, jazz, classical art music, K-Pop, Reggae, and others are available for further study.

Vocabulary

phonograph, phonograph record, radio broadcasting, vacuum tube, audio amplifier

©Copyright 2018-25 by Peter Kun Frary | All Rights Reserved

|